Guest Author: Sharlot Hart, Archeologist and Acting Public Information Officer, Southern Arizona Office, National Park Service

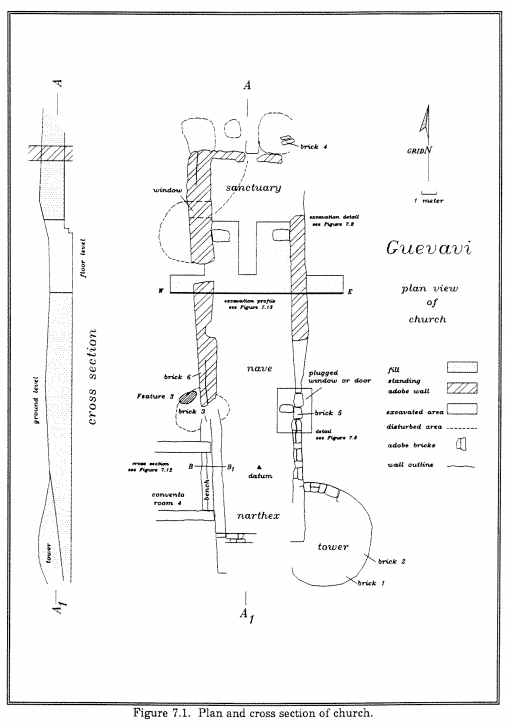

Jeffery Burton’s 1992 report “San Miguel de Guevavi: The Archeology of an Eighteenth Century Jesuit Mission on the Rim of Christendom” has been downloaded from tDAR 41 times (the metadata record that is linked to the report in tDAR has been viewed even more frequently, nearly 1700 times since it was created and the file uploaded in 2010). That’s a lot for an off-the-beaten-path archaeological site that’s usually closed to the public. Mission Guevavi, situated along the upper Santa Cruz River, is preserved by the National Park Service (NPS) as a detached unit of Tumacácori National Historical Park. While the park provides special tours of the site, its remote location and minimal standing architecture makes it less than ideal for visitation from the general public. The figure with this posting (Figure 7.1) is from Burton’s report and shows plan and cross-section of the church at the mission. Guevavi still has so much to add to the archaeological record, though, and it served as the site for a University of Arizona/NPS/Desert Archaeology, Inc. joint field school from 2013 to 2015.

In this light, it makes a little more sense that the seminal report on Guevavi has been downloaded so many times. Digital access to documents like this one is imperative these days. While NPS managers may have a copy of the report in dead-tree (i.e., paper) form, digital access is especially important for our current college students who often prefer digital form. Even for NPS archeologists, digital access is often times quicker than tracking down the park’s copy (Who’s desk did I see that on?). For other researchers and interested members of the public, who cannot easily visit the park office where a paper copy may exist, digital access through tDAR may be the only feasible way for them to read and use the report.

One of the main goals of the recent field school was to research archaeological remains on lands surrounding the NPS-managed core of the Mission area, to get a better idea of the site’s full occupational history. And as an NPS cultural resource manager myself, I’ve necessarily researched the areas around Mission Guevavi to write a culture history ahead of preservation work on the church walls. For all of these efforts, access to and use of Burton’s report has been invaluable.

Burton’s report is part of the Archaeology of Tumacacori National Historical Park project, which includes three other reports, published in 1981 and 1992. It’s a great way to learn about two different missions, both set up along the Santa Cruz River. And while not set up in a specific collection, the reports that tDAR houses, combined with its ability to search for projects using the geographical filter, make researching these unique sites, including Precontact, Protohistoric, Spanish, Mexican, and American Territorial periods, fascinating. The next time you’ve got a free moment, I heartily suggest checking out the archaeology of the Santa Cruz River Valley in Southern Arizona.